- Un gând…

Anca Alexandrescu: Români, vă ordon: Treceți Maglavitul!

- Cine și când a abandonat Ucraina?

În cvasiunanimitate, răspunsul pare a fi: Donald Trump în februarie 2025. Ceva cronologie ar putea nuanța răspunsul cu pricina. 31 decembrie 1991. Uniunea Sovietică dispare oficial. 1994 – Budapesta. În acel an, noul stat independent Ucraina era cea de a treia putere nucleară a lumii. Statele Unite și Regatul Marii Britanii se angajează să apere integritatea teritorială a Ucrainei, în cazul unui atac din partea Rusiei. Rusia semnează și ea Memorandumul prin care se angajează să respecte integritatea teritorială a Ucrainei. Ucraina semnează Memorandumul prin care renunță la armamentul nuclear – eroare de proporții. Memorandumul nu avea, legal, vreo valabilitate, era mai degrabă un fel de Gentlemen’s Agreement, or, în politică, asemenea înțelegeri sunt rareori respectate, mai ales când este vorba de gentlemeni moscoviți. 2011 – Într-un filmuleț documentar, Vladimir Putin, pe atunci prim-ministru, declara că „destrămarea URSS a fost cea mai mare catastrofă geopolitică a secolului trecut”. Din acel moment nu mai putea exista niciun dubiu cu privire la intențiile lui Putin după ce va redeveni președinte de jure; de facto a fost în tot timpul rocadei cu Medvedev. Occidentul s-a făcut că plouă. 26 martie 2012, Seul, Nuclear Security Summit. Președintele american Barack Obama pare a adopta poziții ferme. Nu realizează că un microfon e deschis și-i spune președintelui rus Dimitri Medvedev, care tocmai își termină mandatul: „This is my last election … After my election I have more flexibility…”(„Astea sunt ultimele alegeri pentru mine… După alegeri voi putea fi mai flexibil”). Medvedev îi răspunde încântat: „I will transmit this information to Vladimir” („Îi voi transmite această informație lui Vladimir.”) Și i-a transmis-o. Vladimir a înțeles mesajul. 18 martie 2014. Rusia anexează Crimeea. Barack Obama se ține de cuvânt și este mai mult decât „flexibil”, continuînd să se ascundă după o așa-zisă doctrină („Leading from behind”), mai potrivită pentru un club de „băieți veseli”, decât pentru „liderul lumii occidentale”. Washingtonul își etala încă o dată resursele de ipocrizie. Printre altele, Putin s-a prevalat de un anume lucru. Și anume, ajuns Secretar General la PCUS, Nichita Sergheievici Hrușciov hotărăște ca, printr-un decret al Prezidiului Suprem al Uniunii Sovietice dat la 19 februarie 1954, să schimbe Crimeea din teritoriu al Republicii Sovietice Socialiste Federative Rusia în teritoriu al Republicii Sovietice Socialiste Federative Ucraina. Poziția Kremlinului a fost că, în momentul în care Ucraina și-a declarat independența, Crimeea, teritoriu rusesc, trebuia restituită Federației Ruse. Înțelegerea care funcționase din punct de vedere teritorial-administrativ în timpul URSS, spune Moscova, nu mai avea nicio legitimitate după ce Ucraina își declarase independența. Cui aparținuse Crimeea înainte de a fi devenit teritoriu rusesc este o discuție care pe Putin nu-l interesează. 24 februarie 2022. Putin lansează un război criminal împotriva Ucrainei. Soldații Federației Ruse săvârșesc atrocități greu de imaginat pentru o Europă a secolului 21. Sancțiunile nu-l sperie pe Putin. Un sondaj indică exact ce vor să ignore occidentalii – 86% dintre respondenți sunt de acord cu deciziile lui Putin. Ceilalți – străinii și cei 14% de nemulțumiți interni – n-au decât să dezaprobe ce face liderul de la Kremlin. Putin are, de multă vreme, trei mesaje clare pentru Occident. Primul – Uniunea Sovietică, a cărei destrămare o deplânge, a fost Rusia Mare, iar „cea mai mare catastrofă geopolitică a secolului trecut” trebuie îndreptată. Rusia Mare trebuie reîntregită. Al doilea, transmis prin vocea ministrului de externe Serghei Lavrov – Statele Unite nu mai sunt singura putere dominantă a lumii. Al treilea – jocul de societate „Nu e adevărat, n-am împărțit lumea în zone de influență” dispare. Moscova spune cu voce limpede: „Ba am împărțit-o, numai că e nevoie de o reajustare.” China – devenită mare forță economică, financiară, tehnologică și armată – susține proiectul. Februarie 2025 nu a venit din senin. Este o verigă dintr-un lung lanț al erorilor comise de Occident în evaluarea Rusiei și în pregătirea răspunsurilor adecvate față de un apetit imperial la care Rusia nu a renunțat niciodată. Nici pacea negociată, nici continuarea războiului nu-i vor putea înapoia Ucrainei teritoriile ocupate de Rusia. Deocamdată asta este trista realitate. Și-atunci? Ce e de preferat – pacea negociată sau continuarea războiului? Povara uriașă a răspunsului stă pe umerii unui singur om – Volodimir Zelenski. Abandonarea Ucrainei nu s-a produs într-o zi de februarie a anului 2025. Ea a fost un proces. Dacă sprijinul care i-a fost acordat în ultimii ani Ucrainei se va dovedi a fi venit prea târziu, responsabilitatea ar trebui împărțită în mod echitabil.

- Părerologii?

Vârtejul pe care-l provoacă Donald Trump, deciziile lui pe care mulți le condamnă pe bună dreptate, alții nu le înțeleg, felul în care ele pot afecta locurile în care trăim, brutalitatea stilului – diplomație fără stil diplomatic etc. fac mai din noi toți peste noapte un soi de analiști politici foarte vorbăreți. Nu realizăm că imensa majoritate constituim cea mai numeroasă armată a planetei – Părerologii. E, bine, îmi spun, să facem scurte pauze și să-i ascultăm/citim și pe cei care știu ceva mai mult decât noi, oameni care au dovedit, decenii la rând, că au știut să citească exact mersul lumii, chiar dacă prognozele lor nu s-au adeverit întotdeauna. Astăzi, George Friedman, autor care nu mai are nevoie de prezentări pentru cei preocupați – cât de cât – de științe politice, studii geopolitice, viitorologie – invitat de Ed D’Agost Partner, COO, & Macro Team Leader – Mauldin Economics. Mai jos, câteva idei extrase din răspunsurile lui Friedman:

– Politicienii nu sunt magicieni.

– Președinții nu fac ce și-ar dori să facă. Fac ce trebuie să facă.

– Politicienii devin președinți pentu că înțeleg realitatea – cel puțin pentru o vreme.

– Când vechile reguli nu se mai potrivesc realității, ele, normele osificate trebuie sparte.

– În timpuri anormale, președinții se ridică și încalcă legea. Andrew Jackson, F.D. Roosevelt asta au făcut. Roosevelt s-a confruntat cu un sistem bancar prăbușit. A știut că dacă nu intervine în primele 100 de zile… A încălcat legea pentru a salva situația. Asta pare să facă și Trump astăzi. Vrea să facă cât mai mult în primele 100 de zile, fiindcă știe că și Congresul, și Curțile vor fi după el să-l oprească.”

– Groenlanda? Canada al 51-lea stat al Statelor unite ale Americii? Golful Americii, nu Golful Mexic? Subiecte alese spre a distrage atenția de la subiectele cu adevărat reale.

– Trump încearcă să redeseneze/să rearanjeze lumea. El consideră că actuala ordine mondială este irațională. N-am votat cu Trump. La nivel personal, nu-mi place Trump, dar el știe ce face.

– Europa este un loc, nu o națiune. Nu poți conta, nu poți pune bază pe fragmentele din care este compusă.

– Rusia nu e la pământ, dar acest război a slăbit-o.

– Nu, Ucraina nu va deveni membră NATO.

- „CAN TRUMP TROLL HIS WAY TO A PEACE DEAL IN UKRAINE?”

Temperamentul, bătu-l-ar vina! În cazul administrației Biden e bine, sănătos, că Trump nu vrea să audă de „principiul continuității”. Foarte puține lucruri din politica internă și externă a administrației Biden merită să fie continuate. Mai vedem, mai așteptăm… În urmă cu câteva zile, Victor David Hanson – istoric remarcabil și spirit conservator – intervine în schimbul de replici/polemica dintre alți doi conservatori – Vicepreședintele J.D. Vance și Niall Ferguson (THE FREEPRESS, 21 februarie 2025). Cum pentru cei care nu au abonament, textul de pe THE FREE PRESS nu se deschide integral, l-am copiat și îl postez mai jos. Încă o dată – problema nu este de a fi pro-Trump sau anti-Trump, ci de a înțelege puncte de vedere diferite de ale noastre, firește, fără obligativitatea de a le accepta. De data aceasta diferențe de opinie între doi, ba chiar trei conservatori americani.

VICTOR DAVID HANSON: CAN TRUMP TROLL HIS WAY TO A PEACE DEAL IN UKRAINE?

Two conservatives whom I like and greatly admire—Niall Ferguson and J.D. Vance—were this week involved in a social media dispute over President Donald Trump’s preliminary broadsides about the three-year Ukrainian quagmire, whose combined dead, wounded, and missing mark the worst bloodbath in Europe since the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942 and 1943.

As we approached the three-year-anniversary of the war, Ferguson faulted President Trump for calling Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky a „dictator” and claiming that Ukraine had „started” the war. In his criticism, Ferguson contrasted Trump’s words to George H.W. Bush’s unambiguous „this will not stand” response to news of Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait. And he added that students of history will naturally ask why the current Republican president did not react in the way Bush had in faulting and then ejecting from Kuwait the clear aggressor: Saddam Hussein.

Ferguson’s observation drew a heated response from Vice President J.D. Vance. He countered that the historical parallels were ossified (e.g., Bush in 1990 was confronted with entering a war against a paper-tiger Iraq, Trump with inheriting in mediis rebus a horrific, three-year Verdun-like stalemate directly involving one of the world’s largest nuclear powers). Margaret Thatcher wrote in her memoirs that she had to reassure Bush in a phone call after Saddam’s invasion that „this was no time to go wobbly,” and reportedly had also said the same thing to him at an Aspen conference: „Remember George, this is no time to go wobbly.”

Vance continued with a long rebuttal to what he called „moralistic garbage” and the „rhetorical currency of the globalists.” Aside from the humanitarian need to stop the carnage, Vance offered five counterpoints for why peace negotiations are needed now after three years of ghastly stalemate with no end of the war in sight: 1. The Europeans are terrified because they selfishly have focused on their own social welfare domestic interests—on the assumption that their security needs would ultimately and always be provided for by the U.S., which itself has neglected its own domestic front and will do so no more. 2. Given Russia’s huge advantages (in GDP, population, natural resources, and area) neither Ukraine nor Europe—at its current arms shipments—realistically will defeat Russia. 3. The U.S. has leverage on both Ukraine and Russia, and should naturally use it for its own sake as well as the vital interests of others. 4. To end the senseless war, the U.S. naturally must talk to all sides, including Vladimir Putin. 5. The war is increasingly injurious to U.S. military readiness, and contrary to its strategic interests in seeing China not allied with Russia. And the war’s continuance is neither advantageous for Ukraine, nor Europe nor Russia. 6. Ferguson’s pique arose from Trump’s characterization that Ukraine had „started” the war, and not the Russians, who invaded Ukraine for a third time on February 24, 2022. And from the idea that Zelensky was a „dictator,” with the obvious suggestion, in that regard, that Putin’s authoritarianism is not unique in the conflict.

Of course, Russia started the war. To say otherwise is ahistorical. Trump himself knows that because he rightly had campaigned on just that undeniable truth: that in three of the last four U.S. presidential administrations, Putin invaded other nations’ territory (Georgia/South Ossetia in 2008, Crimea and the Donbas in 2014, and Kyiv and the Ukrainian borderlands in 2022). But he did not do so during the Trump tenure—and for a reason. The obvious motive for Putin’s caution, as Trump has also stated, was that he was deterred—by Trump. Putin feared Trump’s unpredictability as well as his past nonnegotiable redlines, uniformly and successfully apparent in prior preemptive U.S. assassinations of ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and Iranian arch-terrorist mastermind Qasem Soleimani and in Trump’s reactive strikes that devastated the Russian Wagner Group in Syria and ISIS itself. So why, then, did Trump call Zelensky a dictator, and why did he blame him for starting the war? On the first accusation, that Zelensky is a dictator, Trump’s surrogates have often pointed out that he had postponed a scheduled election. Opposition media, political power, and free speech are muted under Zelensky’s martial law. And in many cases, he has suppressed habeas corpus.

Zelensky’s supporters counter that Winston Churchill in World War II also did not hold an election until after the end of the European theater, after half a decade of no elections. But that is somewhat disingenuous because upon ascension as prime minister in May 1940, Churchill soon created a coalition wartime government of allies, rivals, and opponents, analogous to Israel’s bipartisan war cabinet—but not similar to Zelensky’s veritable one-man show. While the British government censored antiwar media, there was far less suppression of individual liberties under Churchill than in current Ukraine. Franklin Roosevelt, of course, held elections in both 1940 and 1944, both after the start of World War II and after the U.S. entry into it against Germany, Italy, and Japan. American elections continued during the Civil War, World War I, and the Korean and Vietnam Wars.

Trump’s further point was probably to remind Zelensky that his country has lost a quarter of its population to exoduses, and that its economy is in shambles, it is running out of soldiers, and it is now solely dependent on Trump’s willingness to continue critical military and economic aid. And Trump would likely think that Zelensky should remember that he is no longer the rock star of 2022, when Ukraine bravely repelled the Russians, the world was infatuated with the T-shirt-wearing ex-comedian, Europeans boasted of unlimited aid to come, and many naively thought the conflict was all but over. So that was then, and more than 1 million combined casualties are now—a horror that Trump suggests Zelensky keep in mind as he issues demands to America, his last remaining reliable patron. But as for the second accusation, why did Trump say Zelensky started the war when so often he himself has emphasized that Putin began all the Ukrainian wars in other administrations but not his own? Five reasons. One, Trump is likely Art of the Deal-trolling Zelensky to get real, in the manner he raised the idea, but really was not going to invade Panama, purchase Greenland from Denmark, and/or absorb Canada. But he did want to gain the attention of all three countries. And he did so, given Panama did cancel its provocative canal agreements with China, Denmark did decide to invest more seriously in Greenland and is rearming, and Canada announced it would begin securing its porous border with the U.S. And all parties are better off for Trump having said what he said. (And indeed, recent reporting suggests that Trump is simultaneously seeking a minerals deal with Zelensky to win back some of the billions sent to Ukraine, a concession that may follow as intended from his trolling.) Two, Trump also is likely alluding to controversial accounts that shortly after the survival of Kyiv, during several iterations of peace talks in March 2022, Zelensky’s representatives met with Russian delegations and reportedly passed on terms that were more favorable then, during a Russian setback, than now, after a Russian recovery. It should be noted, however, that at that early date, polls showed a majority of Ukrainians believed they could force Russia back without negotiations—although now half the population favors some sort of negotiations with Russia to end the war. Three, Trump may be alluding as well to even more controversies concerning the original casus belli of 2014. The Obama State Department reportedly had sided with Europhiliac forces inside Ukraine to work against the elected, though likely unpopular, pro-Russian Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, who was forced out of office. Trump may be raging that had Ukraine remained neutral, and not flirted with both EU and NATO memberships, then Russia, along with Ukraine’s Russian-speaking minority, might not have felt so insecure with a hostile Western border now much closer to Russia. Four, Trump has a long, unforgiving memory. The president is well aware that in 2016 the then-Ukrainian ambassador to the U.S., Valeriy Chaly, in an op-ed, inappropriately warned Americans of the dangers of a Trump candidacy and openly sided with Trump’s then-opponent Hillary Clinton, who spread false stories that the Trump campaign had colluded with Russia. Trump also likely remembers that in September 2024, the Biden administration foolishly air-dropped Zelensky into the critical swing state of Pennsylvania, where in Scranton, Biden’s iconic hometown, the Ukrainian president did a media tour of an ammunition factory with Democratic officials—to the outrage of many observers. Zelensky seemed to imply to blue-collar workers that their jobs might be predicated on continued Biden administration military support for Ukraine. Five, Trump is understandably frustrated because he, not Obama or Biden, first sent offensive weapons to Ukraine. Obama’s record with Putin was the humiliating reset, an embarrassing hot-mic offer of an appeasing quid pro quo to Putin, and the Russian invasion of Crimea and the Donbas.

An angry Trump understands that he inherited a once-preventable war. But now he is put in a dilemma, in which he cannot pull all aid from Ukraine and thus be blame-gamed for a humiliating, Afghanistan-like takeover of Ukraine by Putin. Nor can he increase aid to prolong the war and betray his MAGA base and his own campaign promises. Nor can he simply accept the bloodbath continuing at the expense of the U.S. and its interests. I would imagine that Vance and Ferguson—and Trump for that matter—might all reluctantly agree on the general outlines of a needed peace. Peace will require concessions from both sides, the degree and symmetry of which will be determined by which power finds itself in the more advantageous economic, military, and strategic position given the pulse of the current battlefield. That said, most reasonable observers would concede Ukraine on its own does not have the capability to recover the Donbas and Crimea—which anyway was never the policy of the Obama, Trump, or Biden administrations prior to February 24, 2022.

Ukraine may be armed to the teeth far more lethally than any NATO power, but it will not be in NATO. To suggest that is a dead letter. That Ukrainian NATO membership must remain a talking point for purposes of leverage is absurd, since no one believes it is likely—not the EU, not Russia, not the U.S., and not Ukraine itself. The key sticking point will hinge on whether Putin pulls back to or near his February 24 invasion points, where a demilitarized zone might be established. Will he be willing to tell the Russian people that he prompted a Stalingrad to achieve his aims of institutionalizing the occupation of the Donbas and Crimea and keeping Ukraine out of NATO? Ferguson cited the 1990 Gulf War as the proper historical referent—an allusion that Vance found ridiculous. Perhaps the better comparison in so many ways is the Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939-1940. Joseph Stalin, like the irredentist Putin, after serial demands for territorial forfeiture of some 10 percent of Finland, finally invaded.

Stalin had been convinced that tiny Finland would fold, given an isolationist America, a neutral or pro-Russian Germany under the recent Molotov-Ribbentrop nonaggression pact, and a beleaguered Britain, and a soon-doomed France as the sole surviving major allied powers. But like Ukraine, Finland fought back heroically and fiercely, capturing the imagination of the world, as the League of Nations expelled the USSR to the general applause of the free nations. Yet the final story of Russia at war is that it often fights poorly in the beginning of its conflicts—and, if on distant expeditionary missions, poorly in the end as well, as against Japan from 1904 to 1905, Poland from 1919 to 1921, and Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. But eventually Russia does prevail in deadly, exhausting wars on its European borders or inside Mother Russia, as Charles XII, Napoleon, and Hitler learned. So by February and March 1940, overwhelming Russian numbers and equipment finally ground down the gallant Finns. Their iconic field marshal, Carl Mannerheim, wisely then sued for peace. Finland surrendered roughly what Stalin had originally wanted but otherwise kept itself intact and autonomous, won worldwide praise, and managed a difficult but mostly prosperous neutrality between east and west for the next 85 years.

The world remembers the glorious Finnish resistance of 1939 that cost Russia 400,000 casualties. But it mostly forgets that the Finns eventually would have lost the war and their country in 1940 had they not negotiated an end to the horrific conflict. In modern terms, it is unfortunate that Ukraine may suffer the same position. Zelensky will be praised for his wartime leadership that helped save Kyiv from Russian absorption, but he will likely be forced to give up the Donbas and Crimea, and must then hope to reestablish future deterrence based on Ukraine’s current record of military prowess. The key is that no one knows whether Russia can be forced back to its February 23, 2022, borders. But on the other hand, Ukraine, the EU, the U.S.. and Russia seem increasingly reluctant to see another 1.5 million collective casualties over what might have otherwise been negotiated, while China watches its once main rivals waste their human and material resources.

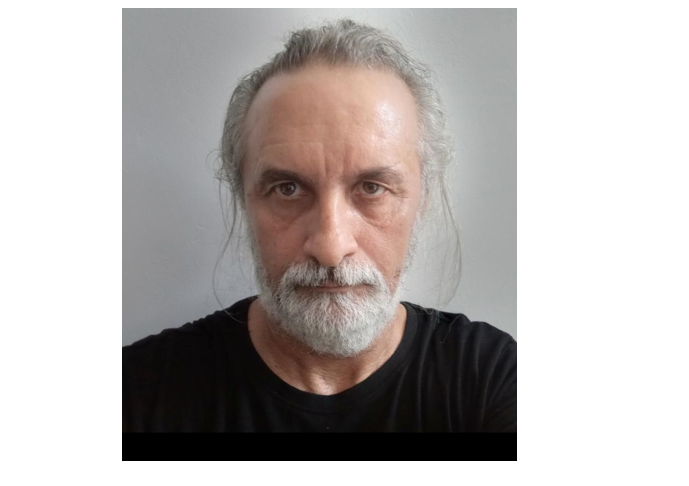

Dorin TUDORAN este un mare poet, eseist, publicist și dizident politic român. Suntem onorați că Domnia Sa a acceptat să publicăm, în Gazeta DÂMBOVIȚEI, texte din ULTIMA PĂLĂRIE („poate că nu știu exact ce sunt, dar știu foarte bine cine nu sunt”…) și nu numai…

Facebook

Facebook WhatsApp

WhatsApp TikTok

TikTok